As the construction sector works to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions, one tool is rapidly gaining importance: limit-values that define how much climate impact new buildings are allowed to have. Across the Nordic countries, governments and industrial actors are developing their own versions of such limit-values, but they are doing so using very different methods.

In their recent CISBAT 2025 publication, “Reduction Roadmaps: methods of determining limit-values for climate impact in construction,” PhD candidates Toivo Säwén and Anna Wöhler from our group collaborated with architects at Wingårdhs and Krook & Tjäder, as well as researcher Ida Karlsson from the Department of Space, Earth and Environment.

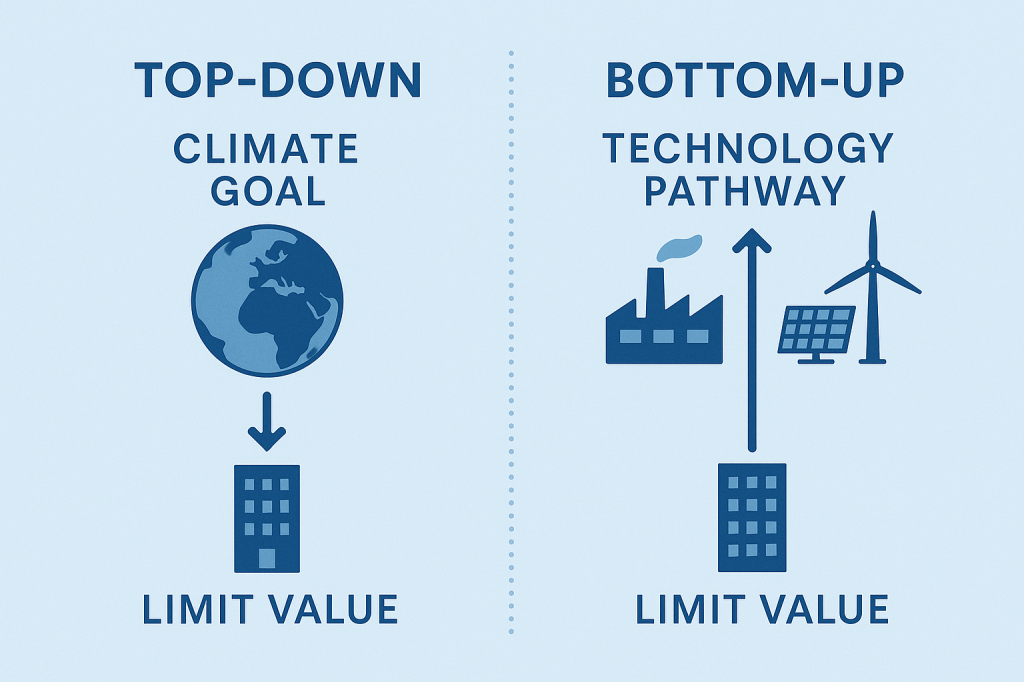

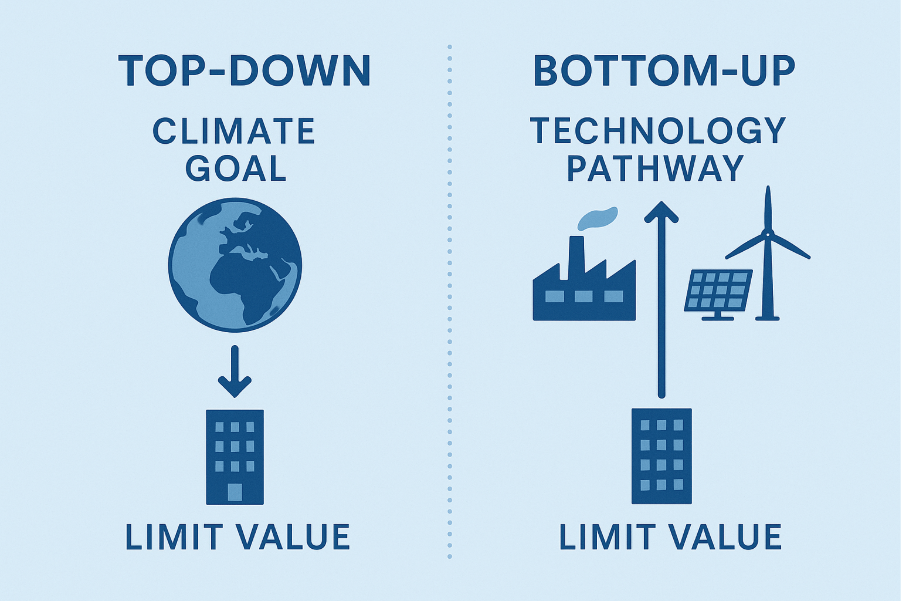

The study reviews 14 initiatives across Sweden, Denmark, Finland, and Norway and identifies 27 methodological choices that shape how climate limits are set. It highlights a strong divide between bottom-up, technology-based approaches and top-down, climate-budget-based approaches and discusses why a hybrid method may be needed to meet long-term climate goals.

We spoke with Toivo to learn more about this work, its findings, and its implications for future climate regulation in the construction industry.

- What motivated the study? Your paper shows that many countries and organisations are now defining “limit-values” for the climate impact of new buildings, but using very different methods. Why is this a challenge for the construction sector?

The time to act in response to the climate emergency is now, and the construction industry has a great responsibility to act, both in Europe and worldwide. National and transnational regulations like limit-values play an important role here to ensure a level playing field for actors in the construction industry. Basically, these limit-values ensure that there can’t be economic benefits to delaying the transition to less climate intensive practices in the built environment. What we see now is that these regulations are developing in very different ways, both in different countries, and on a EU level. First of all, this means a lot of parallel efforts that could be avoided if joint methods were developed. Secondly, it makes comparisons between countries difficult, raising questions about the fairness of the regulations if some countries are more ambitious than others.

- You reviewed both legislative limit-values and industry-led Reduction Roadmap initiatives. What differences did you observe between these groups?

We can highlight two differences. First off, we saw that the industry-led initiatives are generally more ambitious than the legislative, national approaches. This makes sense as the industrial initiatives often include organisations that have already come a long way and want to make sure that their investments in the transition continue to be relevant as regulations evolve. Secondly, we see that industrial initiatives are much more likely to consider a carbon budget perspective, whereas the national initiatives mostly focus on incremental improvements based on currently available technologies. This is what we refer to as the difference between top-down and bottom-up approaches – top-down means defining carbon budgets that take planetary boundaries into account, while bottom-up means focussing on currently available technologies. Our main message is that a balance between both is needed for limit-values to be accepted by actors, while being effective in combating the climate emergency.

- Among the 14 Nordic initiatives you analysed, were there any examples that stood out, either for being especially ambitious or especially conservative?

Well, we see different processes in different countries. For instance, Denmark has very rapidly introduced limit-values for new construction, whereas Sweden has introduced mandatory climate declarations without setting limits. This means industrial initiatives in Denmark have focussed on campaigning for appropriate legislative limit-values, whereas industrial actors in Sweden have instead self-organised, committing to lower impacts without having to wait for the introduction of legislation. The large scale effect of these different approaches remains to be investigated. We can see that the transition in Denmark is happening on an industry-wide level, whereas in Sweden it is spearheaded by certain more ambitious organisations while others have largely continued business-as-usual.

- A core finding of your work is the divide between bottom-up (technology-based) and top-down (climate-budget-based) approaches. Why do these two approaches generate such different limit-values for the same type of building?

The harsh reality is that the carbon budgets available to remain in line with the Paris agreement, limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, are rapidly running out. This means the top-down, climate-budget based approaches that are in line with the Paris agreement are really restrictive. Meanwhile, purely bottom-up approaches can aim for a gradual reduction over the upcoming decades that emphasises minimising or eliminating negative economic impacts. The chosen course is of course in the hands of democratic political processes, but these decisions need to be taken based on transparent information from the scientific community. That is why we are arguing for taking into account both bottom-up and top-down approaches to understanding limit-values, so that decision-making can be informed both by the social, economical consequences, and the consequences for the global environment.

- The paper recommends hybrid approaches to bridge the gap between technological feasibility and climate science. What could a practical “hybrid” method look like in the Nordic context?

The key idea we are proposing for practical implementation is that methods exist for benchmarking proposed approaches based on their alignment with carbon budgets. This means that decisions on any proposed limit-values can be taken while aware What we currently see in proposed legislation is that the climate perspective is missing, which means it is impossible for decision-makers to know if the legislation will actually be effective in contributing to meeting climate goals. So the hybrid approach means developing alternatives for limit-values that have acceptance among industry actors, and then benchmarking those alternatives based on carbon budgets so that the environmental consequences are made clear when a decision on what legislation to introduce is made.

- You note that even ambitious limit-values may not be sufficient without reducing overall construction rates and making better use of existing buildings. How should this insight influence climate strategies in the construction sector?

Most limit-value proposals currently in place set limits for emissions per square metre. This can lead to some very strange conclusions, for instance it can often be easier to reach limit-values for a larger building as impact from the most climate-intensive building components are spread out over a larger area. We also know that the least climate-intensive building is the one that is never built. Limit-values per square metre can’t affect whether a building is needed or not. This means limit-values need to be accompanied by better legislative opportunities to make sure that construction efforts are prioritised based on societal needs, not only based on economic considerations.

- Finally, what do you hope policymakers and industry actors take away from your study?

Our main idea is that bottom-up, technology-based approaches can coexist with top-down, climate-based approaches. By applying multiple perspectives, decision-making can be scientifically informed. We also want to point to the great amount of work being done to develop robust limit-values, and urge policymakers and organisations to learn from approaches in other regions and nations, so that the climate transition of the built environment can be an arena for collaboration rather than competition.

The Reduction Roadmaps study provides a comparison of how climate limit-values for buildings are currently being developed across the Nordic region. By revealing the many methodological choices behind these values and the significant differences they can produce, the work lays a foundation for more harmonised, transparent, and scientifically grounded climate regulation in construction.

We thank Toivo Säwén for sharing insights from this collaboration, and we look forward to seeing how this research continues to support the transition toward a low-carbon built environment.

Read more

CISBAT Conference paper by Toivo and Anna: Link to paper

Interview by Chalmers department of Architecture and Civil Engineering – Toivo and Anna on the Reduction Roadmap: Link to article